![]()

![]()

TRMA Tech Feature of the

Month

September 2005

Coal Ports and Coaling Outriggers

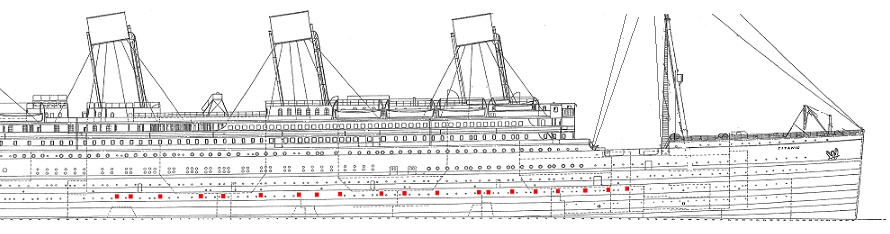

Filling the bunkers on the Olympic-class ships required a massive amount of coal. The bunker capacity on Titanic and her sister was 6,611 tons, all of which had to be loaded by hand from coal barges that were brought alongside the ship. As the bunkers were located in the lower decks, extending down below the waterline, the ships had to be constructed with a means of expeditiously loading such large amounts. For this purpose, passenger ships were typically constructed with doors in the side of the hull called coal ports, which opened through the hull into the spaces directly above the bunkers.

(Modeling note: on the original issue of the 1:350 Minicraft, the hull was cast with an "X" on each door. This is incorrect, and was corrected in the updated kit, but if you have an original kit you'll need to sand off the "X"s.)

Titanic's

coal ports were of a unique design imposed by the requirements of their location:

as they had the lowest doors in the hull, any leakage through them would be

serious, and any flooding would be disastrous. The doors for had to

be very strong, and when closed and sealed had to effectively become part

of the hull itself. These doors had to be able to withstand and remain

sealed against heavy seas, contact with tugboats, hull stresses and other

forces.

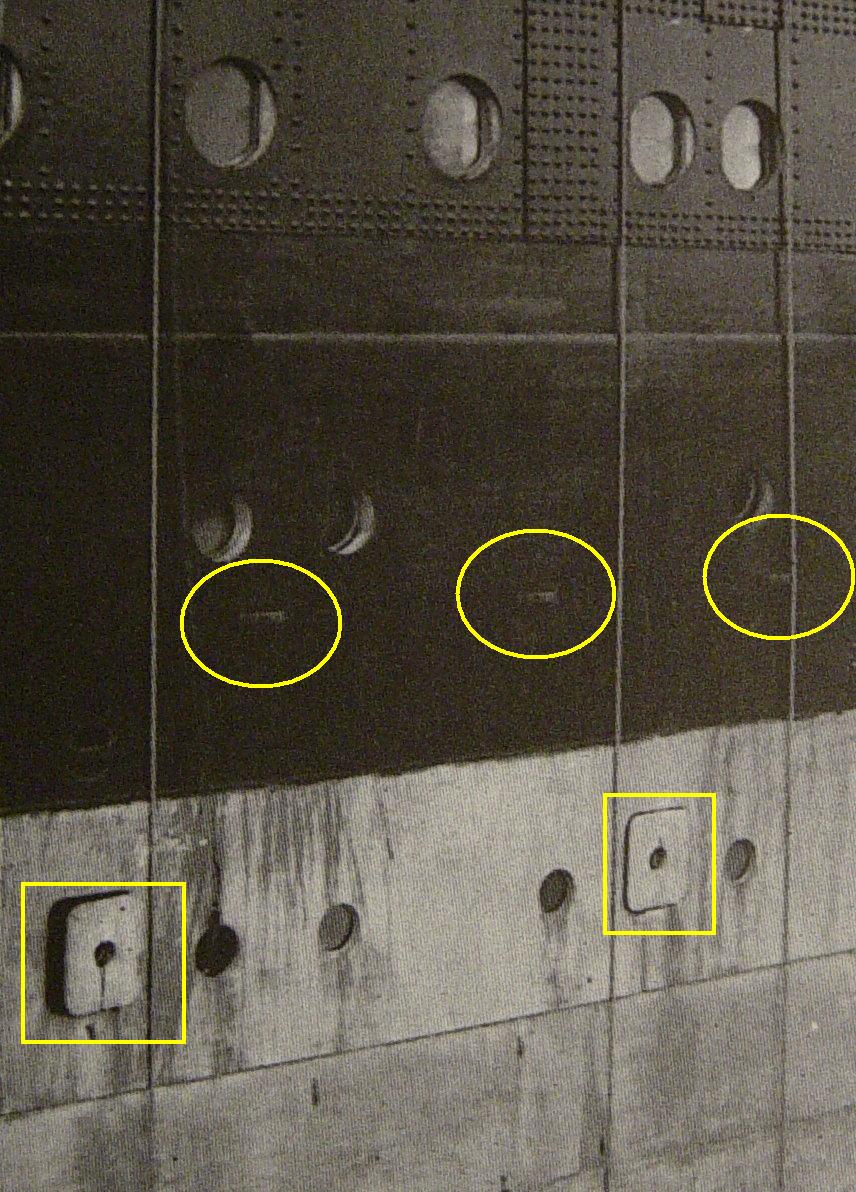

The door was secured in the closed position by a heavy cast steel brace, called a strongback, that spanned the inside of the door opening when closed. A large-diameter threaded steel rod extended out from the strongback through the door, with a large nut on the outside. When the nut was tightened (screwed down) the door was pulled tightly against the opening. A gasket with red lead waterproofing, applied before the door was closed, completed the seal. (Modelers looking for an extra element of detail can drill a small shallow hole in the center of each coal port, not penetrating all the way through, to replicate the recess for the strongback nut.)

The hinges were of a type that allowed the door to swing out and completely clear of the opening when in use. The coal was brought alongside the ship on barges and a platform, or stage, was rigged in front of each port to large eye cleats above and to either side of each port. (The term "eye cleat" is used loosely here - the actual name is not known.) These cleats are readily visible in the closeup photo below right. (Modelers demanding extra detail can replicate these cleats by cutting extremely small tabs of styrene plastic and gluing them to the hull at where the two strakes of shell plating meet.)

The photograph of Olympic, below left, shows the barges in place and the stages rigged preparatory to coaling. Once the doors were opened, coal chutes would be rigged in front of the ports to assist in transferring the loads. In this photo the doors have not been opened yet.

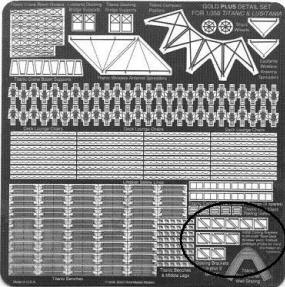

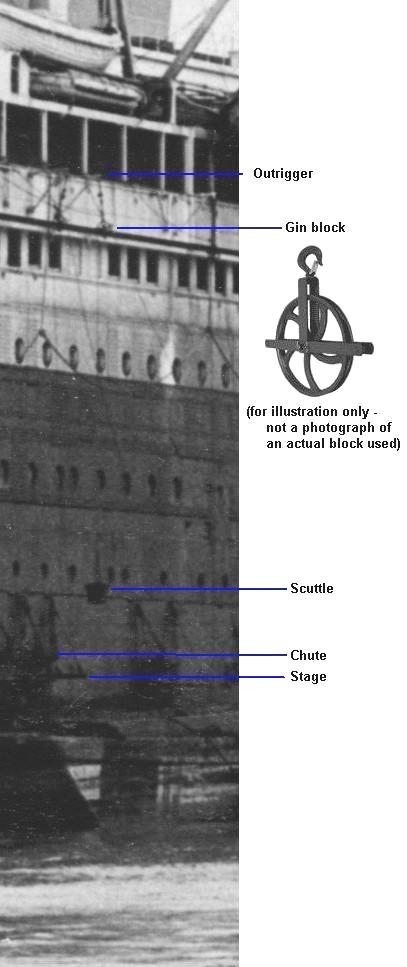

On the coal barges the coal was shoveled into scuttles (large bucket-like containers), and hoisted up to the coal ports by means of blocks (pulleys) hung from the coaling outriggers. The outriggers were the triangle-shaped brackets along the superstructure just below the promenade deck windows, seen in Loren Perry's model below left. These were hinged, and swung in against the hull when not in use. When needed for coaling (or painting the hull) they would be swung out.

For Minicraft modelers, the plastic outriggers in the kit can be replaced by photoetched brass parts for much finer detail (below right).

During coaling, the outriggers were rigged with a type of pulley called a gin block. (These were the same type as used for the cargo span over the forward well deck.) At each coal port, a line would be run from the coaling barge up through the block and then back down to a large coal scuttle. The coal would be shoveled into the scuttles by hand, and hoisted up to the coal ports where men on the stages would tip the loads inside. From there, trimmers would distribute the coal evenly throughout the bunkers.

The

photograph detail at left is of Olympic coaling during her wartime

service, and illustrates what's described above.

The

photograph detail at left is of Olympic coaling during her wartime

service, and illustrates what's described above.

Loading thousands of tons of coal at the end of every crossing was an exhausting, filthy job, and when the last shovel of coal had been loaded, the work still wasn't over. There was a lot of cleaning up to do, since a fine film of coal dust had been deposited just about everywhere. Scott Andrews,: "Not only did the exterior surfaces of the ship required complete an thorough cleaning after coaling was completed; many places in ship's interior were usually left coated with a layer of fine, black dust as well, and this happened in spite of the best efforts of the crew. While coaling, every sidelight, door and window was shut, every bit of ventilation throughout the passenger and crew accommodations was shut down and all the vent heads on deck were covered up, and still this dust found its way into nearly every corner of the ship. When the switch to oil fuel was made, it wasn't only in the fueling process itself that the Company saved time and money."

Have a question on this item? Post it on the TRMA Titanic Forum.

Historical endnote to this photo (Scott Andrews, TRMA): "This is from her early war service. During this period only her white paintwork was "grayed-out", and not the entire hull. Note that where the glass is raised, the windows have been painted out, the normal practice employed during both world wars when painting ships for transport duty; this helps prevent light "leaks" at night and eliminates the glint of reflected sunlight from calling further attention during the day. The (grey) paint is often how the Olympic and other liners appeared all over when they were in the transport service -- filthy, grimy and rust-streaked; only the still-black hull hides just how far her appearance has been allowed to go to pot at the time this photo was taken. In passenger service, these ships were constantly, almost fanatically maintained, which is what is required to keep any steel ship looking pristine. But while in government service, these ships were lucky to see a paint brush applied only every so many months."

Copyright ©2005 Titanic Research & Modeling Association