In 1996, I received the Academy/Minicraft model as a Valentine's Day

gift. I was thrilled. At first, I was perfectly happy with the out-of-the-box

model. There was (at that early stage) just one feature that troubled

me: the decks. I was sure that painting them all one color was going

to look bad, but I mixed up some paint and tried it. It looked okay,

but I really was not happy. Next, I experimented with dry brushing

over the solid color. It was little better. At that point, I turned

to the Web for help. The first thing I found was an article in the

archives of Navis magazine that Loren Perry had written about painting

decks. I bookmarked the site, thinking that I would return and download

it. When I finally had the time to go back, Navis had changed the

format of the site and the article was no longer available to non-subscribers.

Since there were no pictures, and since I did not yet know Loren,

I rationalized by assuming that I would not be happy with that solution

either. (I know now from the pictures of Loren's model that it looks

really nice, but in any case, I no longer had the "recipe.")

My next idea was to use wood veneer,

scribed to simulate the planks. I experimented with that, but the

scribing was quite tedious. Unlike plastic, wood has a grain and

it is difficult to ensure that the scribe does not "meander."

Another problem I encountered is that the veneer has a tendency

to split. I also began to realize that cutting the veneer to follow

the decks would be difficult and that it was really too thick, besides.

Worse yet, the grain of the wood was obvious enough that it did

not look realistic at all. My next tactic was to turn to the computer.

I picked up a handful of wooden coffee stirring sticks at a Starbucks

coffee shop and took them home. I taped them together and scanned

them. I reduced the resulting image to the appropriate size and

it looked promising on the computer screen. Unfortunately, when

I actually printed the image, even at a high resolution, it really

did not look like much of anything at all.

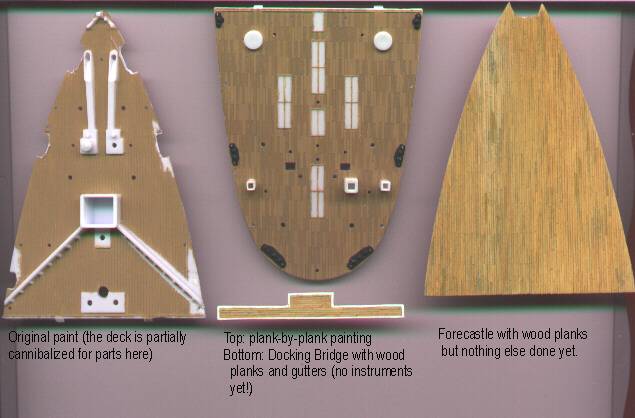

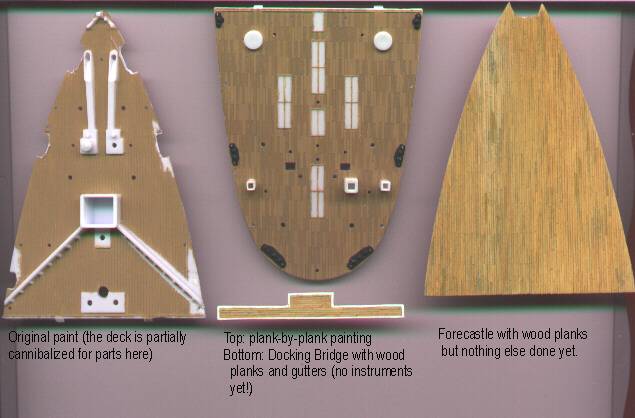

For a while, I spent quite some time

"squinting" at lumber wherever I found it to try to imagine

what it would look like reduced 350 times. I realized that at that

scale, the wood grain would actually disappear, but I noticed that

the planks as a whole were of slightly different colors. Acting

on this observation, I decided to try painting each plank separately.

I mixed up several slightly different colors and set to work. It

took a long time to do this, but in general, it looked better than

anything else I had tried so far. By this time, I was reasonably

sure that I had lost all track of reality. Later, I was relieved

to see that someone on the Titanic

Scale Model page had also come up with the same idea, so I knew

that if I had truly become a raving lunatic, at least I was not

alone.

About a year passed before I again

had time to work on the model. I took the pieces out of the box

and looked again at those decks. It would never do, I decided. Since

I had last done battle with the decks, I had the chance to see a

number of truly beautiful wooden models of sailing ships. There

is something so seductive about all those miniature hardwood planks

gleaming with varnish and I knew that nothing else would ever do.

The problem was devising a reasonable way to accomplish it. I found

that it is possible to buy preconstructed plank-by-plank decking,

but even the tiniest scale was huge by the standards of 1/350 scale.

The manufacturers of all those wonderful wooden ship fittings simply

do not contemplate anything that small. I checked out the availability

of basswood strips, and that was all too big too. Finally, in a

model railroad shop, I found the solution. It came in the form of

scale lumber from Northeastern Scale Models, Inc. I am using the

smallest strips I could find: HO scale 1 x 2's. They are actually

about the right width if you set them on their edges, but I have

just used them flat in a concession to efficiency. Here is the procedure

I have used and it looks great:

- "Stain" the strips with

acrylic washes (you could use watercolors too, or even thinned

enamels). I've used very thin washes in the following artist's

colors: burnt sienna, burnt umber, black, yellow ochre mixed with

a little burnt sienna. I also left some with their natural color.

I have a varying number of each color; most are the yellow ochre

and burnt sienna combination and I used the black wash on the

fewest. You want these washes to be quite thin--it's surprising

how what appears to be a slight variation in color shows up as

a noticeable contrast when you glue the planks down. To keep from

getting too much paint on the strips, I folded a paper towel a

few times and laid the strip on it. Then I set the brush on the

strip and actually slid the strip along under the brush. The paper

towel absorbs some of the color and wipes up the excess.

- Chop the strips into 0.41"

pieces (12 scale feet for the 1:350 scale). I measured this off

with a Vernier scale and used "The Chopper" (available

from Micro Mark if your

local hobby shop does not have it). Be careful when you push the

strips up against the guide. Because of the design of the mechanism

that holds the guide in place and because the strips are so thin,

it is easy to have them slide under the guide and then the pieces

will be too long. It works best if you keep the strips as far

forward as possible. I found I could control three strips at once.

I have not tried cutting more than three at a time, but it might

be possible. At the ends of the strips, you may have pieces left

that are a little longer than the required length. You can risk

your fingers and chop one more time, but I just left them long.

They were handy when I needed to have a really small piece at

the end of a row of planks, since I could handle them easily,

gluing them down and then trimming the excess. As I chopped, I

put all the pieces into a single container, so I would get a random

distribution of colors.

- Prepare the decks. You will need

to get rid of the plank ridges and other premolded markings (such

as the guides for bench and vent placement). Just sand those off.

You also need to cut away other details (such as the cleats on

the forecastle and poop decks). You will need to glue these back

down on top of the planks. You really have to cut them away, since

the wood planks will be too thick up against them. The good part

is that if you mar the decks while doing this, it does not matter,

since you will be covering them anyway. In some cases, it is easier

to just cut a new deck from sheet plastic (e.g., the forecastle

and poop decks) and then cut the parts from the original decks,

rather than doing all the preparative work. Before you obliterate

these (assuming you do not have the CAD

plans), you will need to record their placement, so you can

put things in the proper places. You can draw a plan of the deck,

photocopy it, or scan it, depending on the technology you have

available. If you have the CAD plans, then you do not need to

worry about this part.

- Glue the planks to the deck. I used

WilHold R/C 56 glue, but other glues would work too. The advantage

of this glue is that it does not dry as fast as CA glues, so it

gives more time to position the planks. Whatever oozes up between

the planks is easy to remove (a damp paper towel works fine) and

what remains between the planks takes on a grayish cast (from

the washes) and looks pretty much like caulking). I used a "Glusquito"

(see the Guide) to apply the glue in a thin line. I could lay

down enough glue for about three planks at a time and still have

time to lay the planks before the glue started to dry.

Here are some hints for plank placement:

- First, plan ahead. Try to glue

the planks down in an order so that the last planks will run

off a free edge, rather than running into an obstacle. This

will make laying the last planks easier, since you can just

trim them up against the edge of the deck with a hobby knife.

- Start by drawing a line down

the center of the area you are planking. Be sure your line

runs true so that you do not end up with angled planks. You

can draw the line lightly with a scriber or use a fine lead

pencil.

- When I first started doing this,

I was laying the planks "brick-fashion." I glued

down the first row, beginning with a whole plank. On the next

row, I started with half a plank. On the third row, I began

with a whole plank again, etc. In other words, the "overlap"

between any two adjacent rows was half a plank. I soon discovered,

however, that it looks better to be a little more random.

I reasoned that if I were actually planking a deck, I would

be most likely to start out the next row with whatever I had

left over from the previous row (it would take less sawing

and would use the planks more efficiently). I found that visually,

it looked much better. Brett Anthony has since kindly provided

me with better information. To quote him directly: "Typical

wood-ship practice would be to lay planks so the butt joints

are staggered in quarters. In other words, with 12' planks

the ends of adjoining strakes would be 3' apart. So if you

start from some bulkhead with a full plank, the next row would

start with a 3 footer, the third row with a 6 footer, and

so on."

- As you glue a row, use a short

metal ruler or other stiff straight edge and push it against

the row to keep it running straight and true and to keep the

planks snugged up against each other.

- Clean up the surface. First, I used

a hobby knife to carefully lift up larger globs of excess glue

that oozed up between planks. Then I used a damp paper towel to

wipe away the rest of the glue (do not get the paper towel too

wet). I actually used the kind of heavy duty paper towels you

can buy at hardware stores for paint clean up rather than the

grocery store variety, because they are much more durable and

don't leave as much lint. Next, sand the deck so that all the

planks are at the same height. Use a sanding block and fine sand

paper (400 grit works fine). Surprisingly, you do not lose the

"stained" color when you do this. It soaks into the

wood far enough to remain even after sanding. If you are not happy

with the color at this point (too much contrast or a predominant

color that you think is too red, too yellow, or whatever), you

can apply a thin wash over the entire deck at this point.

- Finish and seal the deck. I used

Dull Cote to seal the deck once I finished it. You can either

spray or brush it on.

Be forewarned. This is tedious work,

I really think it was just as tedious to paint the individual planks

and the results were not nearly so nice. You can do much of the

work "assembly-line-fashion", so it really is not so bad.

Now, I have a plan for hull plates that involves sardine cans...

|